Paul Harris: Working Between Forms

Paul Harris (1925-2018) exemplifies the back and forth between art and artist, between place and culture, and between male and female dynamics. Although his art defies categorization, Harris worked within the context of other artists and art movements.

Post-war American artists bore witness to dramatic changes in the second half of the 20th century. Harris, having served in World War II, explored mediums with an eye toward this understanding. He can be placed on the latter edge of the Abstract Expressionists, and he honed his skills through his education at the New School in New York City, visits with Willem de Kooning, and his work under Abstract Expressionist guru Hans Hofmann in Provincetown, Rhode Island. As his work matured, he began to explore the figure with his sketches, bronzes, and fabric sculptures, for which he is best known.

Some have placed Harris “at the edge of Pop Art,” without the reliance on obvious commercial objects of the genre. During the 1970s, he lived in California and knew many of the artists in the Bay Area Figurative Movement, who reincorporated subject matter into their work as a reaction against abstraction. Harris’ art never really veered toward the conceptual art of the latter 20th century (with the exception of his string sculptures); instead, he chose to side with the figurative work, while still maintaining the abstract discipline in his pastel drawings.

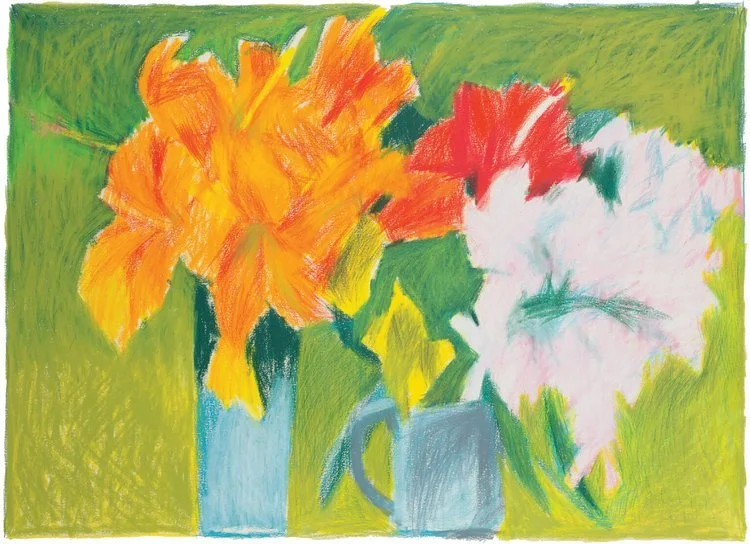

ORANGE HIBISCUS, PINK OLEANDERS 1983 | ART CRAYON | 15.5 X 21.5 INCHES

Primarily a sculptor, Harris created female cloth figures that put him on the map in New York City’s vibrant AbEx scene in the 1950s, and he had his first solo show at the Poindexter Gallery. “My dad considered himself more of a sculptor than a painter,” says his son Nicholas Harris, a Bozeman, Montana-based architect. “His identity was really based on sculpture. Fabric and bronze were the two essential expressions of his work.”

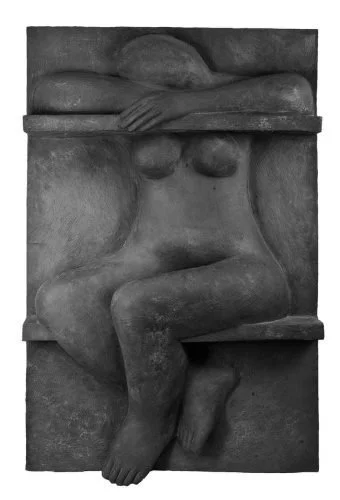

Harris’ fabric sculptures incorporate color composition, voicing a young artist’s concerns with the figure in the midst of abstraction. He often melded figures with pieces of furniture, offering a courageous emotional tether to being in the moment, while the bronzes represent the mature artist, a seasoned mind, and a man wrestling with more complex questions within a larger context.

Over his 60 years of creating and teaching, Harris embraced an interdisciplinary artistic practice, leaving behind an extraordinary legacy of artwork. He found meaning and purpose in the shape of a bronze, the visceral feeling of string, the strength of color, and the delightful incongruity of his sewn figures. As Harris wrote, “Sculpture must engage, arouse, disturb, irritate some tiny particle within us that nothing else touches.”

Harris’ bronzes ring with texture. Made first in wax, the hand of the maker remains evident on every piece, from a cup and saucer to an abstracted vase of flowers to the larger figurative pieces that resonate more like a presence than an object. “Sometimes it feels like he’s reaching into the subconscious more with the bronzes than what he does in his prints and drawings,” says Nicholas. “The bronzes became an exploration of his intuitive world. In many of the pieces, he is capturing the ordinary where, at times, he brings a sexuality to them; and at other times, he gets us to see a deeper meaning in these everyday objects, asking us to pause and reflect for a minute.”

One of Harris’ larger-than-life bronzes, Woman on the Beach — a partial figure with high, tented legs — will be installed this year at the Bozeman Sculpture Park. “That’s a strong piece precisely because it represents both the younger artist mourning the loss of his mother and the older artist who comes to this piece in a more complex way,” Nicholas says, referring to the artist’s loss of his mother at a very early age. “It’s a memory of his mother on the beach, walking under her legs as if it was a bridge.” The piece will be placed along the main walking path, where people can experience an intimate connection with it.

NORISSA RUSHING | 1970 | CLOTH ON WOOD AND METAL | 85 X 72 X 60 INCHES

THE VISITOR | 1969 | STUFFED CLOTH ON ASSISTED CHAIR |34 X 23 X 24 INCHES

Harris’ works on paper remain in continuous dialogue with his sculptures, bringing patterns and textures into a two-dimensional relationship. A direct conversation with the theories of Hofmann, Harris’ activated surfaces carry an almost electric energy to the compositions. The art crayons offer him an immediacy that reaches back to his childhood. As Harris expressed in a KWMR radio interview in the 2000s, “I remember in sixth grade, the teacher wanted a lot of things made that she would use the next year and the next. I didn’t do much work in her class except make these big drawings. I became very accustomed to crayons, and I’ve never been able to let them go. Crayons are still my best friends in making drawings and I don’t think it will ever end. The [ones I use] are a bit better than school crayons.”

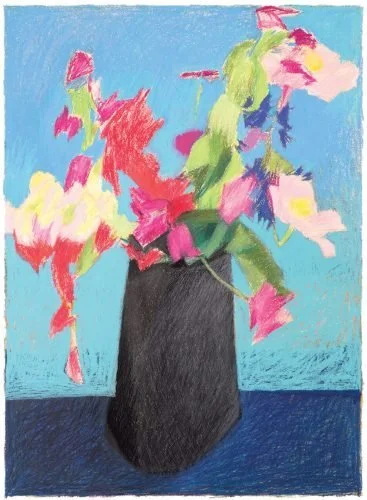

In Harris’ Black Vase, the flowers themselves are not an exact replica. Instead, the piece evokes an idea of flowers — of sweet peas and perhaps columbine — and the joy of beholding something fragrant and exquisite. Looking a bit closer, one can see that he creates layers through the vigor of his colors. For this, we can refer to Hofmann’s idea of an activated surface. Harris once said, in response to Hofmann’s influence, that he wants the subject of his drawings to shatter the background. In this piece, jagged petals jab at the shifting blue behind them, and the shadow of the table disappears into the backdrop, disrupting the logic of the piece.

Harris’s wax and pigment pieces are full of movement, his crayon work both frantic and methodical as it zig-zags across the drawing’s surface. As stated in the laws of thermodynamics: “Energy cannot be destroyed, but is converted from one source to another.” The energy Harris bestows on the drawing is still there — conveyed forever on the picture plane.

OONA NUDE| 1989 | BRONZE |63 X 41 X 12 INCHES

KNIFER RIVER WOMAN I 2011 | BRONZE | 29 X 16 X 13 INCHES

Although Harris was considered part of the Bay Area Figurative Movement, as noted in Thomas Albright’s Illustrated History, the Harris family has a strong connection to Montana, having visited the region frequently. In fact, Harris taught sculpture at Montana State University and worked in a one-room schoolhouse just south of Bozeman for a time. “It was a landscape that Dad was really connected with,” says Nicholas. “He resonated with the mountains. My mother [Marguerite Kirk] grew up in Bozeman. Her parents and aunt were well-established in the community going back to my mother’s great-grandfather, who homesteaded in Bozeman in the 1880s.”

Taken as a whole, Harris’ work reaches outward and pulls inward, as he courageously pokes against the thin skin that separates art and artist, challenging the notion of limits. By embracing the incongruities of flatness and three-dimensionality of line and form, context and content, Harris invites the viewer to consider what it means to be vulnerable.

Through the course of his career, Harris was a Fulbright professor in Chile, a MacDowell Colony resident, a Guggenheim recipient, and a visiting artist at the Rinehardt School of Sculpture, in Baltimore, Maryland. His work has been exhibited in major museums across the country, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (with the exhibition Sculpture of the Sixties, which also traveled to the Philadelphia Museum of Art), the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York, the 1965 New York World’s Fair, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In addition, Harris taught at many prestigious art schools, eventually landing at the College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, California, from which he retired in 1992.

Today, the Paul Harris Art Collection is housed in a gallery just outside of Bozeman that shows his work on a regular basis, often combining his pieces with those of other historical and contemporary artists. In addition, several of Harris’ bronzes as well as his lithograph series, The Shut-In Suite, can be viewed at Medium Gallery, located at 619 North Wallace in Bozeman. For more information about Medium Gallery, visit savinc.net/medium-gallery. For more information about the artist, visit paulharrisart.com.

Freelance art writer and author Michele Corriel earned her master’s degree in art history and her Ph.D. in American art. She has received a number of awards for her nonfiction, as well as her poetry. Her book, The Montana Modernists: Shifting Perceptions of Western Art, is available from Washington State University Press.